A Review of Abeer Seikaly’s Work in Innovating with Traditional Knowledge

Born in 1979, Abeer Seikaly is a Jordanian-Palestinian interdisciplinary artist and thinker. In 2002 she received her Bachelor of Architecture and Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Rhode Island School of Design. After working as an architect in luxury retail for a few years, she received her big break and international recognition in 2013 for a new tent design (Weaving a Home) that offered up a solution for creating homes for displaced communities.

In her work she tries to reimagine architecture as a social technology that “has the power to redefine how we engage with and within space.” She is the co-founder of Amman Design Week and ālmamar, a residency program and cultural space which hosts culinary experiences, interactive exhibitions and tents. Her work has been exhibited in galleries and museums around the world, including Darat Al-Funun in Jordan, the MoMA in New York, the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

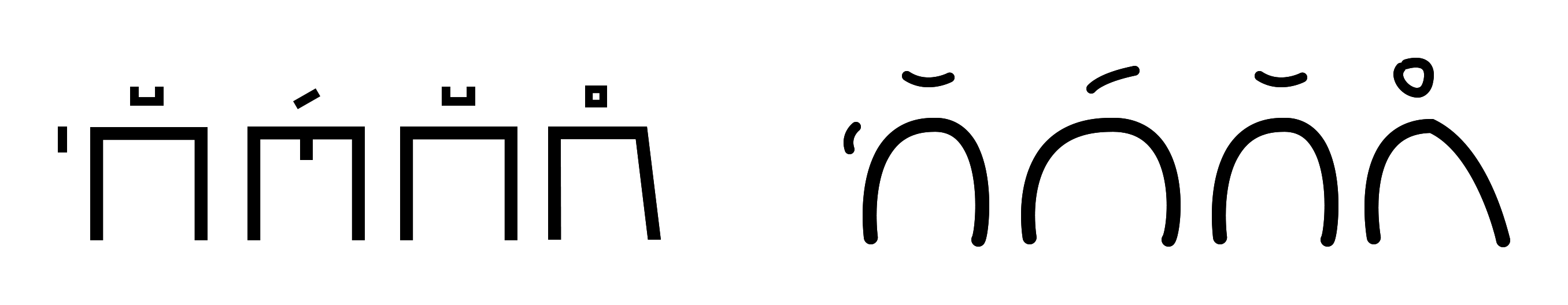

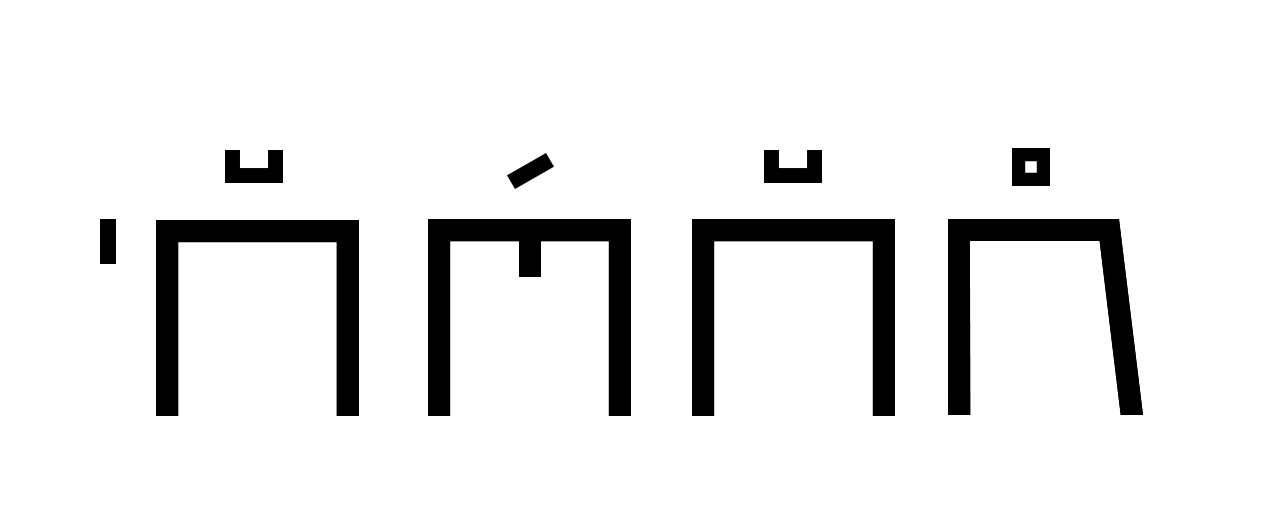

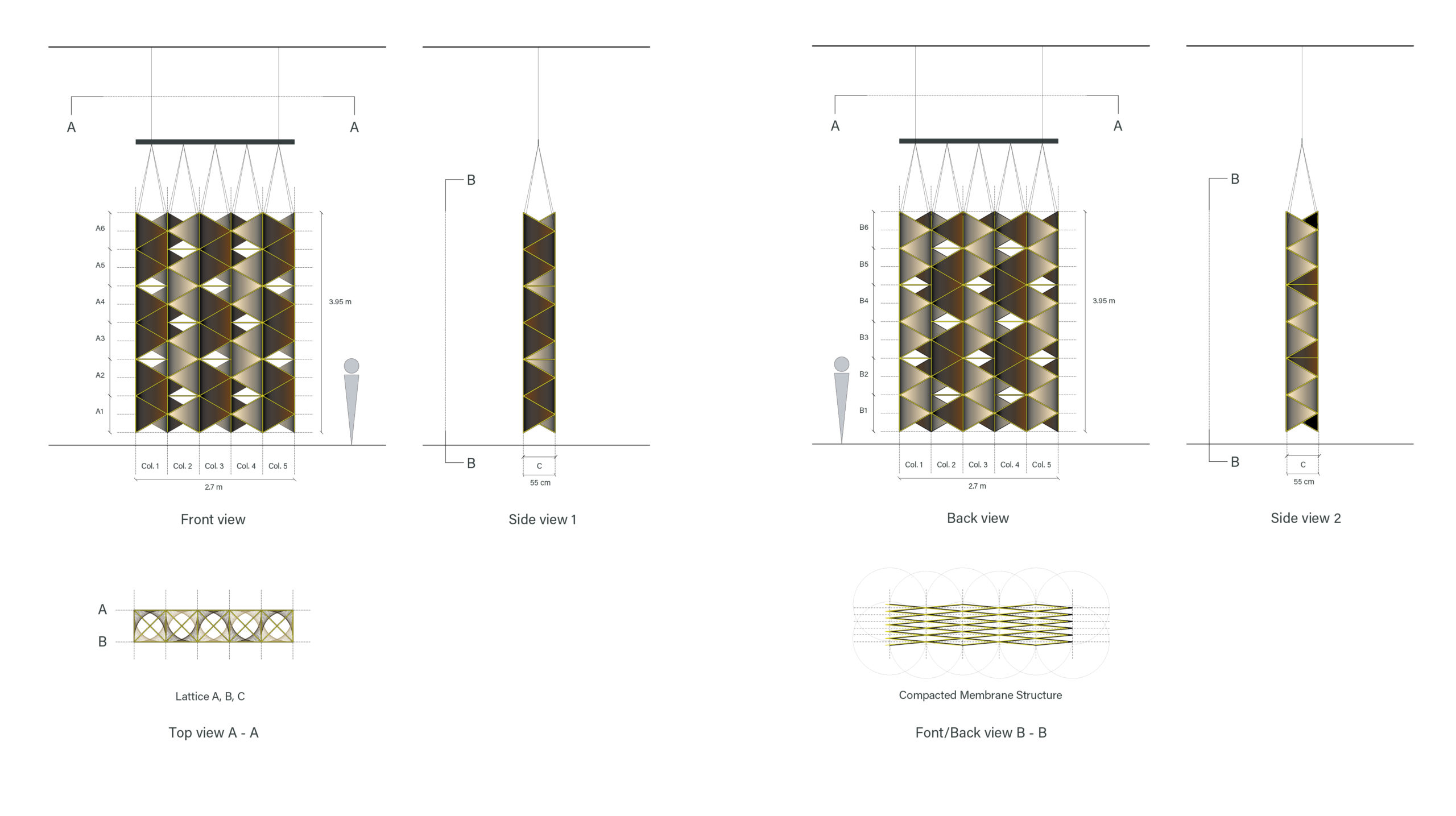

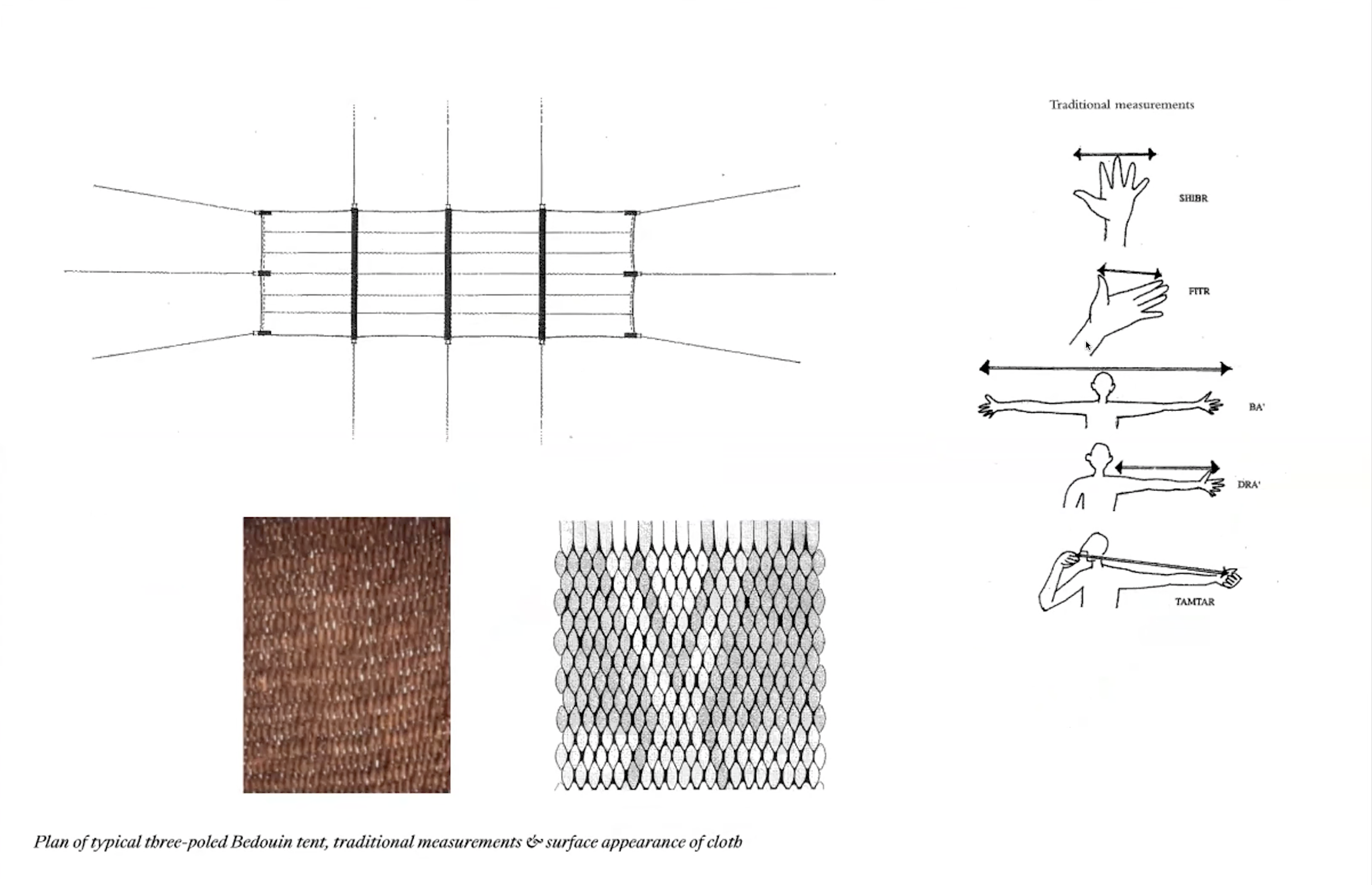

Meeting points is a structure and installation presented Seikaly at the Amman Design Week in 2019. The installation from the 2019 exhibition includes what Seikaly calls a “self-structuring tapestry” consisting of a lattice structure and a geometric hand-knit pattern made from a mixture of goat hair and jute yarn. The structure is comprised of three cells that are repeated on the x and z axis. Each square of the structure was knit separately then stitched together using different seam patterns while laid out flat. To create a 3D structure, two layers connected to each other where needed. Finally, wooden rods were threaded in the seam patterns with metal connectors for the joints. The resulting structure is what Seikaly calls a “stable, self-structuring material system” and shows alternately colored “columns” that resemble the proportions of the Bedouin tent’s roof.

Referencing beit al-shaar (the Bedouin tent), Seikaly tries to recenter structures that have been marginalized as “architectures without architects.” The project utilizes this knowledge held by women and indeed is a result of a collaborative project with Bedouin women across the Kingdom of Jordan. Indeed, when looking at the shapes which make up Meeting Points, they clearly reference the patterned Bedouin rugs and it is very clear they were taken directly from Seikaly’s family heritage.[1]

I decided to focus on Seikaly’s project because it offers an opportunity for architecture that is directly connected to the form of weaving and fabric and centers invisible architects, that is the people who are the main builders of most human shelters. In addition, it recontextualizes women’s work as an art form and expertise that developed over centuries and that can still be advanced today in the context of modern architecture.

In the 2019 exhibition at Amman Design Week, the tapestry was hung from the ceiling of the main hangar, suspended quite close to the ground, giving it the appearance of hovering. Although the exhibition included only the architectural form, when presented on her website, Seikaly curates a series of photographs, text and moving images as part of the project presentation. These include documentation of the exhibition and close ups of the form, documentation of the creation process for the materials and for the creation of the structure as well as a plan. This review will focus on the materials presented on the project’s webpage in addition to examining previous iterations of the project and tracing an evolution up until Meeting Points from Seikaly’s previous work. This includes projects such Weaving a Home, The Chandelier and Matters of time. All are projects in which Seikaly begins working with fabric, then exploring and researching the traditional techniques of fabric creation for architectural projects. In addition, this review will examine if and how the artist’s work subverts and challenges the different relationships inherent to the work of an architect/designer (material-structure, nature-designed, designer-community) and engages in new ways of practicing architecture or design when working with communities.

In her essay “Missing Objects” from The Sex of Architecture, Catherine Ingraham says, “women invent a way into architecture by inventing different kinds of practice: small practices, hybrid practices, practices in theory.”[2] This could offer a way of looking into how Seikaly is constructing her practice in a field where Arab women are a minority within a minority. In her work, she presents a way of practice that relies not only on purely traditional architectural sensibilities, and traditional dynamics of client-architect relationship. As she states on her website, her practice always starts with a question about life, the fields within which she operates, about tradition, memory or culture.

There is no end result which includes a building that is finished and done. Instead, there is an ongoing process and exploration that begins with a material, or desire to solve a problem, and then continuously evolves into different iterations and various conclusions that then transform and are carried forward. Having to invent ways of working within a field and creating a hybrid practice in Seikaly’s work means that her roles span various fields and disciplines: constructing, weaving, photography, video, design, architecture. By definition, her work cannot include only capital A architecture. It is through interdisciplinarity that new dynamics are created in the relationship an architect/designer has with the world around them.

Following Ingraham’s observation, in other words, women by nature of entering a field within which they are an overlooked minority have to invent ways of practice that do not reproduce the patriarchal practices which were closed off to them. Practices which emphasized and centered around the individual star architect as the author of a product. This notion of an architect is challenged in in the secondary headline for Meeting Points which define it as “…a call for collaboration towards new models for communal well-being.” The setting which she creates is one which requires more than one sole author, from the get-go the project is defined as one that necessitates collaboration, or as she calls the work done by the Bedouin women, communal practice. It requires a community, even when a designer is the one initiating the conversation and the project.[3]

Textiles and fabric have played a central role throughout Seikaly’s career. Starting with works such as The Chandelier (2011) and Weaving a Home (2013), through Meeting Points and back to the homes project. In the first iteration of the woven home, the double-layered fabric is imagined both as a skin and as a structural element that housed the necessary amenities of modern life. Rotation and movement of the skin revealed openings that would service as entrances or ventilation. In many ways, that was the first attempt (that is ongoing still) by Seikaly to rethink ways in which fabric is used to create architecture and what new role the act of weaving can still have in 21st century architecture.

Beit al-shaar (literally house of hair) is not just a shelter for the Bedouins in the Arab region, and specifically in Jordan. It lies at the heart of the Bedouin lifestyle and is the central place where the “sociocultural values are constantly produced and reproduced.”[4] Beit al-shaar is a symbol of the spiritual life of Bedouins, it is featured in poetry, in folklore songs and in songs that have entered the Arab popular culture. At its core, Bedouin society is a gender-segregated society. The division of gender is very clear in the way the home is constructed. One side of the home (usually the east) is the women’s said of the home (al-mahram). This part of the home is the private part which male guests are not allowed to enter. While the other side (usually the west) is defined as the men’s side. This is the public side of the home (al-shig) where guests (males and foreigners) are hosted.

Historically the lifestyle and the environment of the Bedouins required great adaptability. A mobile life meant everything needed to be packed up quickly and compactly for travel. The ability to orient the home according to the climate and geography was needed and so the tent provided an answer to those needs. Traditionally it was women who were the creators of the Bedouin tent in a labor-intensive process that would have included collecting the goat hair, spinning the hair into ropes, weaving the rugs, stitching them together into different panels and then erecting the structure. The entire process is a communal process where the women of the family and/or the tribe gather to create the home. When considering that traditional ways of measuring were based on the body (Figure 2), the Bedouin tent becomes, in a sense, “a manifestation of the Bedouin woman’s body.”[5]

This is the history of the creation process that Abeer Seikaly centers as the background for the modernization and sedentarization process of the Bedouin community and the effect it has had on the social structure of the community. As in the cases of other traditionally nomadic communities, the Bedouins in Jordan have in the last few decades settled into permanent villages and towns with permanent built structures. This move from the tent to the built house meant that the construction process of the Bedouin home moved from the hands of the women of the tribe to the men.

…foreign migrants have increasingly taken over more traditional forms of female labor in agriculture and animal husbandry, leaving women from particular class backgrounds increasingly confined to the home as the older rationales for their movement throughout the community have disappeared. For Bedouins in particular, housing has been transformed from women’s wealth (a goat hair tent woven by the family’s women) to men’s wealth: the concrete house built with the labor and money of primarily male family members.[6]

Where women once wove, the men now mix concrete, where women once stitched, the men now stacked blocks. In an excerpt from a video Seikaly presented in the 2020 talking Textiles Conference, a woman can be heard saying, “When there is an occasion, they [the men] reach an agreement with the tent guy to get a tent… Nowadays we buy them ready-made… We don’t do them anymore.”[7] In other words, another result of the modernizing process is that the role women had in physically building the home was now also delegated to men.

This tension between the role each gender had/has in the building of the home Seikaly present in the precursor to Meeting Points from 2019, Matters of Time. There she positions quite literally the labor of women and the labor of men opposite each other. Reminiscent of works such as Shireen Neshat’s early video works, the video alternates between close-ups of women shearing goat hair, men operating a concrete mixer. Women rhythmically beat the goat hair with sticks, men lay down the mixture and concrete blocks. Then as the women begin assembling the tent pieces, their actions are staged against the cinematic background of the vast Jordanian deserts. While the men operate in an almost theatrical set, with the bones of eco-lodges clearly visible in the background.[8]

When discussing how the Beoduins are represented in their article on the modern significance of the Bedouin tent, Na’amneh, Shunnaq and Tastasi note how Bedouin culture is presented to tourists so that it “conform in various ways to the Orientalist vision Westerners have of the Bedouin. Bedouins are still largely represented as exotic and primitive and unaffected by social change or technological modernity. Such modes of popular representation are usually produced and reinforced by literary, cinematic and pictorial works.”[9] Any tourist visiting the deserts of the levant, through the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt will at some point be driven into the vast desert by their expert Bedouin guides for a stop in staged tents and an “authentic” experience of riding camels, then sitting and being hosted in a Bedouin tent. This also being an image that the Bedouins themselves uphold for economic reasons.

While Seikaly positions herself as coming from within the culture and history of the Badia[10], and though she defines her research as one looking at how traditional technologies can have a place in the 21st century, in this first iteration of her woven structures, she reproduces the same kinds of images an orientalist mindset comes to expect as Bedouin (Figure 4). There is a sense that the work of women is still positioned in the days of yore. A vast and empty desert, two covered women working under the sun. It is a difficult image to diverge from, the desert in its transcendental scales imposes and almost dictates how it is presented and photographed. With the long years of orientalist image production, the task of producing new ways of seeing and representing the desert is a monumentally difficult one. In many ways this video works falls into the traps of the impatient as it hurries along the slow creation process and recreates these nostalgic desert images.

In any project where the architect claims to be designing and working with a community, there are ethical questions that must be asked about the relationship dynamics between the two sides. The politics of such a relationship where one person claims to have the power and the answers to problems the community might be facing, or in the case of Seikaly’s work, to the disappearing history and craft of the community, need to be discussed and examined closely. Does this new relationship reproduce the same patronizing power dynamics of previous problem-solvers, or does it challenge first and foremost the very idea that a problem-solver, an architect is need in that specific situation, if yes, why?

In fact, Seikaly herself mentions the difficulties of getting the women to engage with the project[11]. By the time she proposed the project to the Badia women she wanted to work with, they had stopped making yarn and weaving tents 20 years earlier and were decidedly not interested in going back to this work. It took discussions, presentation of previous design work and convincing to get them on board with producing the yarn needed and participating in the project. Seikaly does not elaborate on why there was initial opposition to the project and what exactly convinced the women to participate anyway. One can imagine that the hesitancy stemmed from perceived lack of interest or belief that their craft is not relevant anymore[12], or perhaps they were unwilling to go back to the required back-bending labor. The choice to participate would have involved a complex web of considerations that probably would have included in part economic outlooks and most importantly trust in the designer.

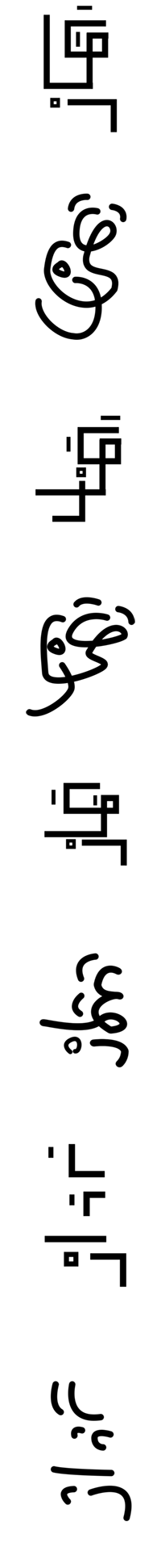

For most of the profession’s history, once the building enters the realm of architecture, women stop becoming part of it, especially when talking about communal architecture such as the Bedouin tents. “Architecture as a profession is based on the need for architecture (as a practice and product) to be the protected domain of the architect.”[13] The mandate to build becomes that of the lone architect and architecture becomes the result of a formal educational course. In that arena, the language used to describe the work that the women are doing becomes doubly important. For as long as it is still described within the realm of crafts, it remains overlooked as another not entirely significant art form that only women engage in. The result is that we have mi’mari, muhandes, mukhatet, banna, mu’awel[14], all participating in the building process now monopolized by men.

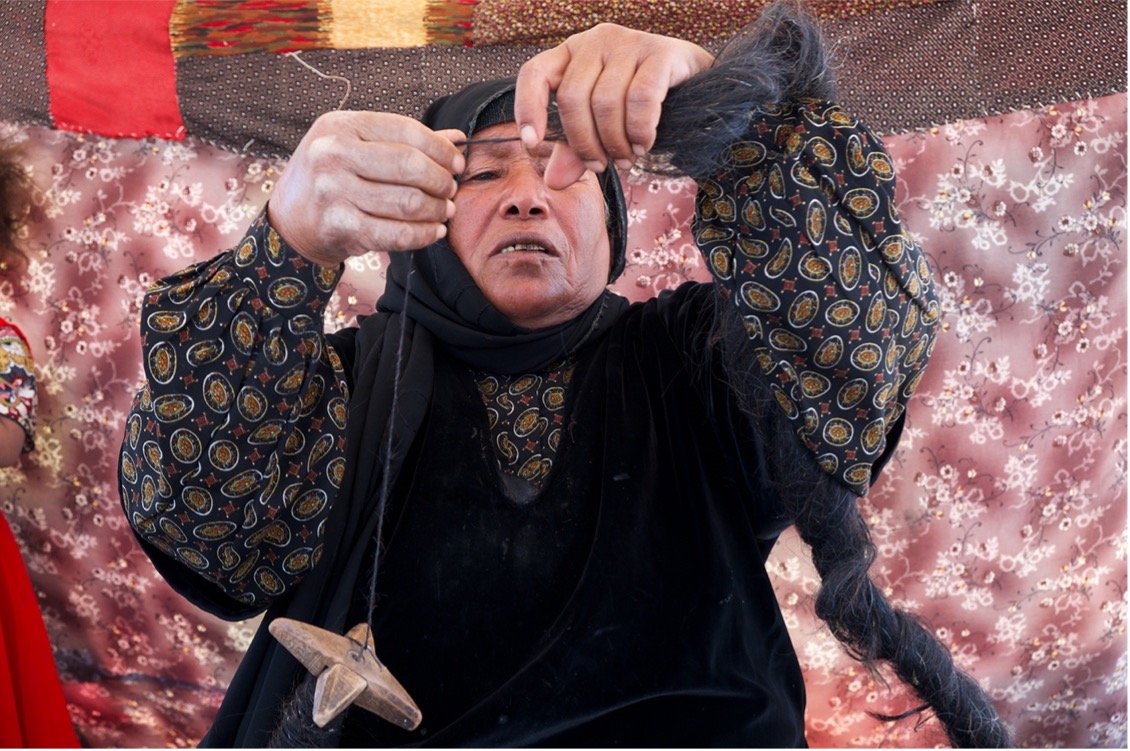

On the webpage, after the initial image showing Meeting Points as it was hung in Amman Design week, in the introductory text, Seikaly begins reclaiming the words related to building practices for the women involved in the tent creation process by defining the work they do as a product of an engineering process, saying, “…the Bedouin Tent is a responsive archetype and performative architecture which should be asserted as a composite material structural design, and attributed to the lineage of Women who have communally and intuitively engineered it.” [emphasis mine.] The images immediately following this line are of close ups of women hands holding spun yarn and a woman’s foot grabbing the spindle with the spun yarn on it. Two smaller images juxtaposed next to each other to complete and complement each other and hint at the entire body behind the work. Immediately after those two images, a photo of a woman caught in the middle of spinning goat hair, against the backdrop of fabric pieces manually sewn together (hinting that this is the inside of a tent or home) takes center stage.

When comparing this image to the ones produced in Matters of Time it seems that there is a shift happening in the way Seikaly thinks about and creates within the scope she defined for the project. Where before the women were constructing the tent in the empty touristic desert, here the woman is twisting the hair, engrossed in her work, but still aware of the camera, in the context of her home, surrounded by the children of the family (right outside the camera frame on the left side). She is embodying what Seikaly calls performative architecture.

By making the connection between the Bedouin woman’s body and the creation of the tent, Seikaly assigns new value to the importance of the tent, to the creation process behind it. She assigns value to the knowledge produced by these women and marks the work they do as a valuable resource. One which the women themselves will be part of adapting to new areas of design and will profit from, thereby gaining back the wealth and capital they once were part of creating.

In her essay on the future of hand-weaving, Annapurna Mamidipudi presents a possibility of both producing tradition and still innovating toward technological change. In the case she presents she describes that the weavers were able to achieve this in two steps, “The first is innovating products, processes, and markets in handloom weaving: the crafting of new knowledge. The second is recasting their innovation as tradition: the craftiness involved in innovating change that produces tradition.” In other words, in order for traditional knowledge and crafts to remain relevant in a modernized, industrialized society, new innovations using traditional skills need to circle back and define these innovations as tradition.

Abeer Seikaly in her work and in the scope she defines for her work lays the ground for innovation that will follow a similar process to the one that Mamidipudi observed in India. Although in Seiakly’s case the creations are not products in the capitalist sense, they are still new creations aimed at new markets, which still use and build on the traditional. In her experiments with the materiality of the goat hair, the jute yarn, weaving and the knit patterns, she is crafting new knowledge. In collaboration with the community whose knowledge she based her work on, she is carving out new areas of use for this knowledge. In the process, by keeping the center of production in the hands of the women who produced this knowledge over centuries, she is creating new income that will make the practice of weaving and innovating on that knowledge sustainable for the community.

Endnotes

[1] See The Chandelier from 2011 where Seikaly presents a photograph of an inherited rug that was woven by her great grandmother.

[2] Diana Agrest, Patricia Conway and Leslie Kanes Weisman, The Sex of Architecture (New York: Harry N. Abrams. 1996), 34.

[3] As a side note, when researching this project online and googling the project name, I found an English-language PDF document of an open call created by the Abeer Seikaly. It appears to have been part of an effort to really open up the avenues of working on this project and to broaden the spectrum of possible future collaborators. The document presents the project as a prototype and proposes a vision for how the project can move forward, “The future advancement of Meeting points, as a communal architecture program aims to become a flagship for how architecture and design processes can act as instruments for social change. A new consciousness attributed to not only what we design and build, but how we choose to design and build.”

[4] Mahmoud Na’amneh, Muhammed Shunnaq and Aysegul Tasbasi, “The Modern Sociocultural Significance of the Jordanian Bedouin Tent”, Nomadic Peoples 12, no. 1 (2008): 151.

[5] Abeer Seikaly, “Meeting Points: From Bedouin Tents to Women’s Community Textiles,” Talking Textiles Conference, October 2, 2020, video, 36:02, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IrG3NGAoHhI.

[6] Hughes, Geoffrey Fitzgibbon, “The Proliferation of Men: Markets, Property and Seizure in Jordan.” Anthropological Quarterly 89, no. 4 (2016): 1081–1108.

[7] Talking Textiles Conference lecture at minute 34.

[8] The rise of eco-lodges as part of desert tourism is something Seikaly references in her talks about her work as an example of sustainability architecture directed at tourists which ignores local traditions.

[9] Na’amneh, Shunnaq and Tastasi, “The Modern Sociocultural Significance of the Jordanian Bedouin Tent,” 153.

[10] The arid and semi-arid desert which comprise around 80% of Jordan and are home to the Bedouins.

[11] Talking Textiles Conference, Abeer Seikaly.

[12] In the same clip from the Talking Textiles Conference, the woman describes how the younger generation do not even know what beit al-shaar is. They do not conceive of the work put into nor make a connection between the woman and the tent. They had grown up in a world where the tents where erected by a contracted man for special occasions.

[13] Awan, Nishat, Tatjana Schneider, and Jeremy Till, Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. (Oxon: Routledge, 2011), p. 28.

[14] Masculine form of architect, engineer, planner, builder and contractor.

Bibliography

Agrest, Diana, Patricia Conway, and Leslie Kanes Weisman. The Sex of Architecture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

Awan, Nishat, Tatjana Schneider, and Jeremy Till. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. Oxon: Routledge, 2011.

Brown, Lori A.. Feminist Practices: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Women in Architecture. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2011.

Coleman, Debra, Elizabeth Danze, and Carol Henderson. Architecture and Feminism. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996.

Hughes, Geoffrey Fitzgibbon. “The Proliferation of Men: Markets, Property and Seizure in Jordan.” Anthropological Quarterly 89, no. 4 (2016): 1081-1108.

Mamidipudi, Annapurna. “Crafting Innovation, Weaving Sustainability: Theorizing Indian Handloom Weaving as Sociotechnology.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 39, no. 2 (2019): 241-248.

Na’amneh, Mahmoud, Muhammad Shunnaq, and Aysegui Tastasi. “The Moden Sociocultural Significance of the Jordanian Bedouin Tent.” Nomadic Peoples 12, no. 1 (2008): 149-163.

Seikaly, Abeer. 2021. A Bedouin Girl in New Haven. December 7. Accessed May 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4oPksZoUpzo.

—. 2019. Matters of Time. Accessed May 2022. https://abeerseikaly.com/matters-of-time/.

—. 2019. Meeting Points. Accessed May 2022. https://abeerseikaly.com/meeting-points/.

—. 2020. Meeting Points: From Bedouin Tents to Women’s Community Textiles. October 5. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IrG3NGAoHhI.

—. 2011. The Chandelier. Accessed May 2022. https://abeerseikaly.com/the-chandelier/.

Swenarton, Mark, Igea Troiani, and Helena Webster. The Politics of Making. Vol. 3. 3 vols. London & New York: Routledge, 2007.

- The Hangar Exhibition | Amman Design Week 2019. November 5. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p9TOmMDIyoY.

Week, Amman Design. 2019. General Highlights | Amman Design Week 2019. December 9. Accessed May 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GxTLK6kituQ.